“Chronic Disease Surveillance and Epidemiology – Part 3: Advanced Methods and Future Directions

Related Articles Chronic Disease Surveillance and Epidemiology – Part 3: Advanced Methods and Future Directions

- Telemedicine And Remote Monitoring For Chronic Illness Care

- Patient Empowerment In Chronic Disease Management

- Gender Disparities In Chronic Disease Diagnosis And Treatment – Part 2

- Comorbidities Associated With Common Chronic Diseases

- Financial Challenges Of Living With Chronic Illness

Introduction

We will be happy to explore interesting topics related to Chronic Disease Surveillance and Epidemiology – Part 3: Advanced Methods and Future Directions. Let’s knit interesting information and provide new insights to readers.

Table of Content

Chronic Disease Surveillance and Epidemiology – Part 3: Advanced Methods and Future Directions

In the preceding parts of this series, we laid the groundwork for understanding chronic disease surveillance and epidemiology. We explored the significance of chronic diseases as a global health challenge, delved into the core principles of surveillance systems, and discussed the essential data sources and collection methods. In this third installment, we will delve into advanced epidemiological methods and explore future directions in the field.

Advanced Epidemiological Methods

While descriptive epidemiology plays a crucial role in understanding the distribution and patterns of chronic diseases, advanced epidemiological methods are essential for unraveling the complex interplay of risk factors, identifying causal pathways, and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions. These methods encompass a range of study designs and analytical techniques, each with its strengths and limitations.

-

Cohort Studies: Cohort studies are longitudinal observational studies that follow a group of individuals (the cohort) over time to assess the incidence of disease or other health outcomes. Participants are classified based on their exposure status at baseline, and the subsequent occurrence of disease is compared between exposed and unexposed groups. Cohort studies are particularly valuable for investigating the temporal relationship between exposure and disease, allowing researchers to establish temporality, a key criterion for causality.

- Strengths:

- Can establish temporality.

- Allow for the direct measurement of incidence rates.

- Can examine multiple outcomes for a single exposure.

- Minimize recall bias.

- Limitations:

- Can be time-consuming and expensive, especially for diseases with long latency periods.

- Susceptible to attrition bias due to loss to follow-up.

- May not be suitable for rare diseases.

- Strengths:

-

Case-Control Studies: Case-control studies are retrospective observational studies that compare individuals with a disease or condition of interest (cases) to a group of individuals without the disease (controls). Data on past exposures or risk factors are collected for both groups, and the odds of exposure are compared between cases and controls. Case-control studies are particularly useful for investigating rare diseases or conditions, as they can be conducted more quickly and efficiently than cohort studies.

- Strengths:

- Efficient for studying rare diseases.

- Relatively quick and inexpensive.

- Can examine multiple exposures for a single outcome.

- Limitations:

- Cannot directly measure incidence rates.

- Susceptible to recall bias.

- Difficult to establish temporality.

- Selection of appropriate control groups can be challenging.

- Strengths:

-

Cross-Sectional Studies: Cross-sectional studies collect data on exposure and disease status at a single point in time. These studies provide a snapshot of the prevalence of disease and the distribution of risk factors in a population. Cross-sectional studies are useful for generating hypotheses and assessing the burden of disease, but they cannot establish temporality or causality.

- Strengths:

- Relatively quick and inexpensive.

- Can assess the prevalence of disease and risk factors.

- Useful for generating hypotheses.

- Limitations:

- Cannot establish temporality.

- Susceptible to prevalence-incidence bias.

- Cannot determine causality.

- Strengths:

-

Intervention Studies: Intervention studies, also known as experimental studies or clinical trials, are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing or controlling chronic diseases. Participants are randomly assigned to either an intervention group or a control group, and the outcomes are compared between the two groups. Intervention studies provide the strongest evidence for causality, as they allow researchers to manipulate the exposure and control for confounding factors.

- Strengths:

- Provide the strongest evidence for causality.

- Allow for the control of confounding factors.

- Can directly assess the effectiveness of interventions.

- Limitations:

- Can be expensive and time-consuming.

- Ethical considerations may limit the types of interventions that can be studied.

- May not be generalizable to all populations.

- Strengths:

Advanced Analytical Techniques

In addition to advanced study designs, sophisticated analytical techniques are employed to analyze chronic disease data and gain deeper insights into disease etiology and prevention.

-

Multilevel Modeling: Multilevel modeling, also known as hierarchical modeling, is a statistical technique that allows researchers to analyze data that are structured at multiple levels, such as individuals nested within communities or schools. This approach is particularly useful for studying chronic diseases, as it can account for the influence of both individual-level and contextual factors on health outcomes.

-

Survival Analysis: Survival analysis is a statistical technique used to analyze time-to-event data, such as the time until the onset of disease or death. This approach is particularly relevant for chronic diseases, as it can account for the fact that individuals may be followed for different lengths of time.

-

Causal Inference Methods: Causal inference methods are a set of statistical techniques used to estimate the causal effects of exposures or interventions on health outcomes. These methods aim to address confounding bias, which occurs when the relationship between an exposure and an outcome is distorted by other factors.

-

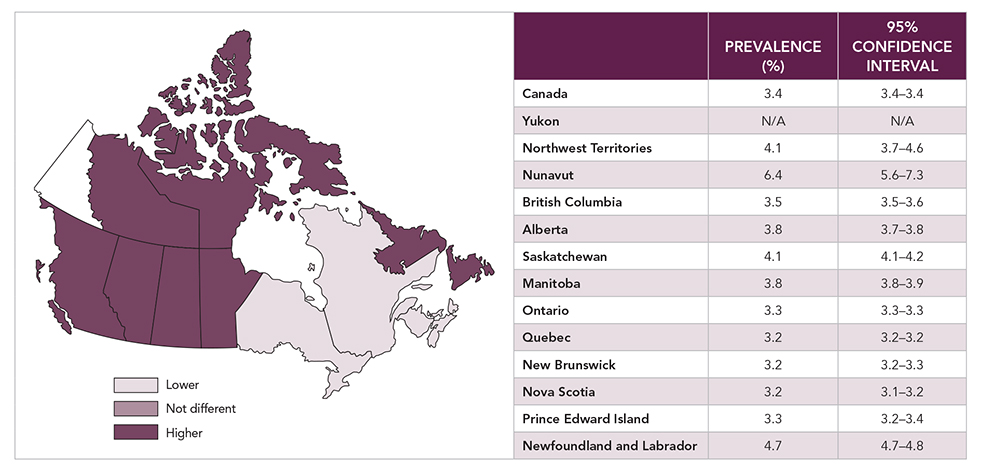

Spatial Epidemiology: Spatial epidemiology is a branch of epidemiology that focuses on the geographic distribution of disease and the identification of spatial patterns and clusters. This approach utilizes geographic information systems (GIS) and spatial statistical methods to analyze disease data and identify environmental or social factors that may contribute to disease risk.

Future Directions

The field of chronic disease surveillance and epidemiology is constantly evolving, driven by advances in technology, data science, and our understanding of disease etiology. Several key trends are shaping the future of the field.

-

Big Data and Data Integration: The increasing availability of large-scale datasets, such as electronic health records, claims data, and social media data, presents both opportunities and challenges for chronic disease surveillance. Integrating these diverse data sources can provide a more comprehensive picture of disease patterns and risk factors.

-

Precision Medicine: Precision medicine aims to tailor prevention and treatment strategies to individual characteristics, such as genetic makeup, lifestyle, and environment. Advances in genomics, proteomics, and other "omics" technologies are enabling the development of more personalized approaches to chronic disease management.

-

Mobile Health (mHealth): Mobile health technologies, such as smartphones, wearable devices, and mobile apps, offer new opportunities for chronic disease surveillance and intervention. These technologies can be used to collect real-time data on health behaviors, monitor disease symptoms, and deliver personalized interventions.

-

Systems Science: Systems science approaches, such as agent-based modeling and network analysis, are increasingly being used to study the complex interactions between individuals, communities, and the environment that contribute to chronic disease risk. These approaches can help identify leverage points for intervention and inform the design of more effective prevention strategies.

-

Global Collaboration: Chronic diseases are a global health challenge, and international collaboration is essential for sharing data, developing best practices, and coordinating research efforts. Global surveillance networks and data sharing initiatives are crucial for monitoring disease trends and responding to emerging threats.

Conclusion

Chronic disease surveillance and epidemiology are essential for understanding the burden, distribution, and determinants of chronic diseases. By employing advanced epidemiological methods, leveraging new technologies, and fostering global collaboration, we can improve our ability to prevent and control these diseases, ultimately improving the health and well-being of populations worldwide. As we move forward, it is crucial to continue investing in research, training, and infrastructure to support the ongoing evolution of this critical field.

Leave a Reply